Introduction to Ocean Research and Scientific Presentation

- Deanna Soper

- Jul 31, 2025

- 7 min read

Want to view this lesson offline? Download the PDF:

Why is the ocean important?

When people hear the word “ocean,” they might first imagine cruises in the Caribbean, surfing the California coast, or watching as the light of the setting sun is reflected off Hawaiian waters. However, these recreational activities simply scratch the surface—ocean systems make our planet habitable. Over half of the world’s oxygen is produced by phytoplankton, microalgae that contain chlorophyll and undergo photosynthesis. These same phytoplankton are also sustenance for the fish, shrimp, and other marine animals that form a significant portion of the global food supply. Other marine resources are used for medicine and technological products. The ocean regulates the climate in two ways: first, it serves as a carbon sink, dissolving more carbon dioxide into its waters than it releases to the atmosphere; second, the movement of ocean currents forms a “global conveyor belt,” by which heat is distributed across the planet.

Sources used:

NOAA. Why should we care about the ocean? National Ocean Service website, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/why-care-about-ocean.html#:~:text=The%20air%20we%20breathe%3A%20The,our%20climate%20and%20weather%20patterns, 2/26/21.

NOAA. What are phytoplankton? National Ocean Service website, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/phyto.html, 2/26/21.

NOAA. The Global Conveyor Belt. National Ocean Service website, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_currents/05conveyor2.html.

How and why do we explore the ocean?

To better understand the answer to this question first watch from 15 min., 30 sec. to 29 min., 20 sec. of the episode from Our Planet titled High Seas. Though the ocean covers about 70% of the world’s surface, both the Moon and Mars have been mapped and studied in greater detail than the ocean floor. This is largely due to the difficulties involved in reaching and observing the ocean. After all, humans can typically only hold their breath underwater for about 30 seconds—a limitation that doesn’t leave much time for exploring! While Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus (SCUBA) can extend that time, generally SCUBA is limited to at most an hour in shallow depths. SCUBA also is limited to certain depths, as most recreational divers' depth limits are 130 feet and scientific or technical diving are generally limited to 330 feet. A challenge in reaching greater depths is the increased pressure.

Methods of ocean exploration that allow scientists to observe the ocean without the aid of a vehicle include snorkeling, free-diving, and SCUBA diving. Though those who snorkel and free-dive are unable to dive further than they can travel on a single breath, SCUBA divers avoid this constraint by the use of the air tank(s) that they carry. The first modern version of this was the fully automatic Aqua-Lung, which was first developed by Jacques Costeau and Emile Gagnan in 1943. SCUBA technology significantly improved the depths which scientists could reach and the duration of their dives.

The first modern technologies that attempted to explore the seafloor were developed in the 1800s. In 1867, dredging operations were conducted off of the coast of Florida. This technique consisted of a ship dragging a net along the ocean floor to collect specimens. However, there were major limitations as animals that were motile could easily swim or crawl out of the nets and small individuals slipped right through them.

In the twentieth century, the invention of submersibles further advanced oceanic exploration. In 1960, the Bathyscaphe Trieste carried scientists to the depths of the Mariana Trench—the deepest point on the planet. The human operated vehicle (HOV) Alvin was launched in 1964 by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to study the deep sea. It is still in use today (after many upgrades and improvements)! Both of these submersible vehicles required human operators within them to control movements and make observations. Alvin can hold two scientists and has manipulator arms for collecting samples from the ocean floor.

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) were first used in the mid-1900s and became significantly more common in the early 2000s. Without human operators having to accompany the vehicle to great depths, ROVs significantly reduced the risk and cost of deep sea exploration. This mode of exploration allows scientists to pilot the submersible vehicle from the safety of a surface vessel while viewing the video footage transmitted by the ROV. ROVs have a variety of sensors, manipulator arms, and sample collection boxes to observe and interact with the ocean.

Sources used:

NOAA. History of NOAA Ocean Exploration Timeline: The Breakthrough Years (1866-1922). National Ocean Service website, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/history/timeline/welcome.html?page=2, accessed 6/1/21.

NOAA. History of NOAA Ocean Exploration Timeline: The Age of Electronics II (1946-1970). National Ocean Service website, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/history/timeline/welcome.html?page=4, accessed 6/1/21.

NOAA. Human Occupied Vehicle Alvin. National Ocean Service website, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/history/timeline/welcome.html?page=4, accessed 6/1/21.

NOAA. What is an ROV? National Ocean Service website, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/facts/rov.html#:~:text=Remotely%20operated%20vehicles%2C%20or%20ROVs,would%20play%20a%20video%20game, accessed 6/1/21.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Underwater diving." Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/underwater-diving, September 20, 2017.

Ocean Research Institutions

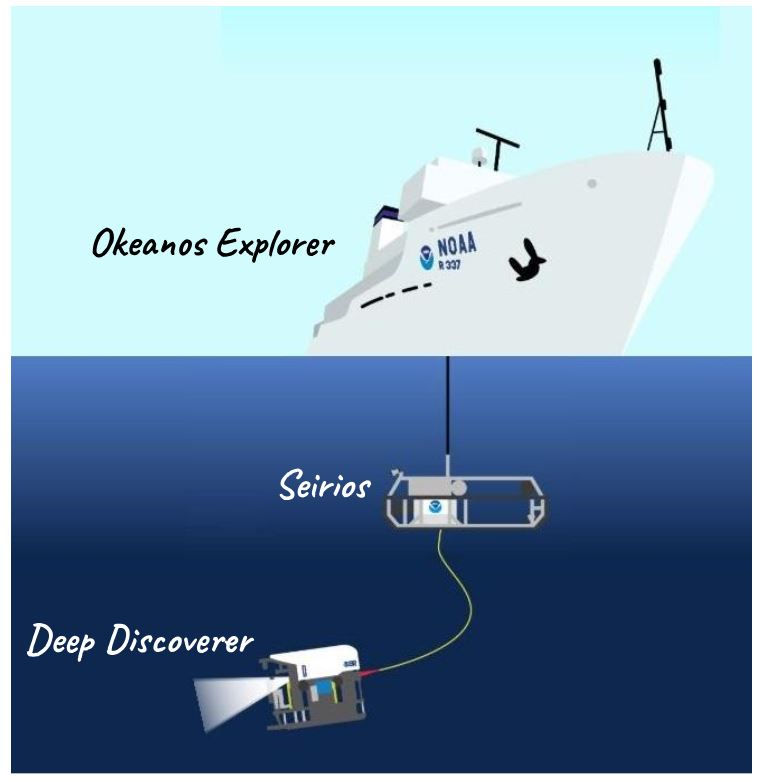

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce with the mission to “understand and predict changes in climate, weather, oceans, and coasts, to share that knowledge and information with others, and to conserve and manage coastal and marine ecosystems and resources.” NOAA Ocean Exploration is specifically dedicated to “innovating, incubating, and integrating research” by engaging in and funding a variety of research expeditions. The deep-sea video footage we will be working with in this course was collected during two NOAA expeditions. Footage was collected using the NOAA ship Okeanos Explorer, the only federal vessel with the sole purpose of advancing scientific knowledge of the ocean, in conjunction with the ROVs Deep Discoverer and Seirios.

The two ROVs were suspended in the water beneath the Okeanos Explorer. Seirios was connected to the vessel by a five mile long steel cable while Deep Discoverer was connected to Seirios by a 30 meter long tether. Deep Discoverer was equipped with lights, video cameras, two manipulator arms, and six collection boxes to film the ocean floor. Seirios provided further lighting, absorbed heave from the ship, collected environmental data, and aided pilots in navigation with attached cameras

Other institutions, like the nonprofit Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), also work with ROV technology to explore the ocean and collect underwater footage. MBARI was created to “achieve and maintain a position as a world center for advanced research and education in ocean science and technology, and to do so through the development of better instruments, systems, and methods for scientific research in the deep waters of the ocean” and to emphasize “the peer relationship between engineers and scientists.” The organization has three research ships and multiple ROVs, and it is located in Moss Landing, California, with direct access to Monterey Bay. The submarine canyon in Monterey Bay allows researchers access to the deep sea without having to travel far distances offshore.

Sources used

Kennedy, B.R.C., Cantwell, K., Malik, M., Kelley, C., Potter, J., Elliot, K., et al. 2019. The Unknown and the Unexplored: Insights Into the Pacific Deep-Sea Following NOAA CAPSTONE Expeditions. J. Frontiers in Marine Science, doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00480.

White, M. P., Kennedy, B. R. C., Amon, D., Messing, C., and Avila, A. M. (2020). Cruise Report: EX-17-11, Gulf of Mexico 2017 (ROV and Mapping). Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, NOAA, Silver Spring, MD 20910. OER Expedition Rep. 17-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.25923/4yc3-an79.

Cantwell, K., Smith, J.R., Putts, M., White, M.P., Cantelas, F, and Bowman, A.. (2020). EX-17-08 Expedition Report: Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts (ROV/Mapping). Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, NOAA, Silver Spring, MD 20910. OER Expedition Cruise Report. EX-17-08, 64 p. doi: https://doi.org/10.25923/pvw9-b391.

NOAA. About the NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. National Ocean Service website, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/okeanos/about.html, accessed 6/1/21.

MBARI. About MBARI. Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute website, https://www.mbari.org/about-mbari, accessed 6/1/21.

Scientific Research Presentation and IMRaD

Scientific papers are published in peer-reviewed journals. After scientists have collected data, they report their discoveries in a manuscript submitted to a journal for publication. If the journal’s editors are interested in publishing the paper, they will send it for review to at least two, sometimes three, other experts in that area of study for a process called peer review. To reduce bias, scientists are not paid to review papers. The review service is considered an important responsibility of being a working scientist.

Scientific papers generally follow a standard format for communicating results called the IMRaD method. IMRaD refers to Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. This is the typical format for oral presentations, poster presentations, and written papers. However, some scientific journals may require that the methods go after the discussion to prioritize the results—interested parties can read on to the methods for a more detailed examination of the work. There is often an additional section known as “supplementary materials.” Supplementary materials fulfill a similar purpose to an appendix, containing additional graphs, tables, or information that pertains to the study but is not integral to the discussion. For the purposes of this lab, you will focus on the primary structure: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion.

In this lab you will learn how to look up scientific literature using Google Scholar. You will analyze the articles that you find to discover what information is contained in each of the sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion.

Looking up scientific papers on Google Scholar

Reach the Google Scholar browser by searching “Google Scholar” in any search engine you are using.

Keep the initial search simple. We will start by searching “Urchin.”

Now let’s say we want to add some specifics to our search. How does global warming affect urchin populations? To optimize our search, we will enter the key words with a + in between, or putting quotation marks around the keyword that we want every entry to include: “Urchin” + Global Warming

Your school may have access to one or multiple libraries, which can further aid our search by including quick access to more articles. Go to settings and find “library links.” You can add your school library or any other libraries you have access to.

Special Note: Other databases can be used to find primary sources, research articles, or secondary sources. ScienceDirect is a database of peer-reviewed literature that is similar to Google Scholar, but may require a library subscription for access.

Comments